-

- World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS). Principles of best practice: compression in venous leg ulcers. A consensus document. London, UK: MEP Ltd; 2008.

- Royal Collage of Nursing (RCN). The nursing management of patients with venous leg ulcers. Clinical Practice Guidelines. London, UK: RCN; 2006.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of chronic venous leg ulcers. A National Clinical Guideline. Edinburgh, Scotland: SIGN; 2010 [cited 14 Sep 2017]. URL: http://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign120.pdf.

- Grey JE, et al. Venous and arterial leg ulcers. BMJ. 2006 [cited14 Sep 2017];332(7537):347-350. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1363917/.

- All-party parliamentary group on Vascular and Venous Disease. Future of Venous Disease: Growing problems, shrinking workforce. June 2023 https://legsmatter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Future-of-Venous-Disease-growing-problems-shrinking-workforce.pdf

- Wounds International. Principles of compression in venous disease: a practitioner’s guide to treatment and prevention of venous leg ulcers. London, UK: Wounds Int; 2013. URL: http://www.woundsinternational.com/media/issues/672/files/content_10802.pdf.

- Wittens C, et al. Editor’s choice — management of chronic venous disease: clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 [cited14 Sep 2017].;49(6):678–737. URL: http://www.ejves.com/article/S1078-5884(15)00097-0/fulltext.

- Franks PJ, et al. Management of patients with venous leg ulcers: challenges and current best practice. J Wound Care 2016 [cited 14 Sep 2017];25(6 Supplement):S1-S67. URL: doi: 10.12968/jowc.2016.25.Sup6.S1.

- Milic DJ, et al. Risk factors related to the failure of venous leg ulcers to heal with compression treatment. J Vasc Surg. 2009 [cited14 Sep 2017];49(5):1242-1247. URL: http://www.jvascsurg.org/article/S0741-5214(08)02007-7/fulltext.

- Neumann HAM, et al. Evidence-based (S3) guidelines for diagnostics and treatment of venous leg ulcers. Eur J Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 [cited 14 Sep 2017];30(11):1843-1875. URL: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jdv.13848/full.

- Ruckley CV. Socioeconomic impact of chronic venous insufficiency and leg ulcers. Angiology 1997;48(1):67-69.

- Urwin S, Dumville JC, Sutton M, et al. Health service costs of treating venous leg ulcers in the UK: evidence from a cross-sectional survey based in the north west of England. BMJ Open 2022;12:e056790. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2021-056790.

- Pugliese DJ. Infection in venous leg ulcers: considerations for optimal management in the elderly. Drugs Aging 2016 [cited 14 Sep 2017];33(2):87-96. URL: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40266-016-0343-8.

- Maddox D. Effects of venous leg ulceration on patients’ quality of life. Nurs Standard. 2012 [cited 14 Sep 2017];26(38):42-49. URL: http://journals.rcni.com/doi/pdfplus/10.7748/ns2012.05.26.38.42.c9111.

- Upton D, et al. The impact of atraumatic vs conventional dressings on pain and stress. J Wound Care. 2012;21(5):209-215.

- Wounds International (2024) Retrospective case series: Application of the M.O.I.S.T. concept to the healing of chronic wounds. Wounds International, London, UK.

Related articles

Read all-

Wound care | 5 min read Rethinking surgical incision care

Surgical incision wounds, often perceived as routine and straightforward aspects of postoperative recovery, have often been overlooked and underemphasised in wound care management. This oversight can lead to suboptimal healing outcomes and increased patient suffering as well as higher costs of care. Recent insights underscore the necessity of re-evaluating incision care and the pivotal role of dressing selection in promoting effective healing. Surgical incisions: The forgotten wound? Within wound care, chronic wounds take most of the focus; they are complex and have prolonged healing processes. As a result, surgical incision wounds, which are acute by definition, may not receive as much attention from a clinical perspective. This disparity arises from the assumption that surgical wounds, being clean and surgically controlled, will heal without as much care or intervention. However, ignoring careful incision care also poses risks, such as complications like surgical site infections (SSIs) and wound dehiscence. Rethinking surgical incision care Rethinking surgical incision care advocates for a paradigm shift in how surgical incision wounds are managed. Central to this shift is the concept of undisturbed wound healing (UWH), which emphasises minimising interference with the wound site to foster optimal healing conditions. This approach involves selecting appropriate dressings that can remain in place for extended periods, thereby reducing the frequency of dressing changes and the associated risks of wound exposure and contamination. Supporting undisturbed healing is the need to create and maintain a moist environment for optimal wound healing, both in acute and chronic wounds. Adopting undisturbed wound healing as a concept means allowing the healing process to progress uninterrupted, not disturbing the wound unless absolutely and clinically necessary2, 3. It is based on maintaining a constant temperature, an optimal moist environment and keeping the wound free of external agents to facilitate the normal wound healing process. How, though, with traditional wound care protocols and conventional dressings, can healthcare providers reach an ideal undisturbed wound healing state? The critical role of dressing selection in promoting UWH Post-op incision care immediately after surgical procedure is critical. Consensus in the literature2 indicate that dressings applied in the operating theatre should remain in place for as long as possible, changed when it is clinically needed rather than based on habits or protocols. Being able to leave a post-op dressing in place for as long as possible means that dressing selection becomes critical. The ideal dressing should maintain a moist wound environment, provide thermal insulation, protect against bacterial contamination, and manage exudate effectively. Simple gauze is insufficient because it requires frequent changes and does not have the capacity or long-wearing properties of advanced dressings. Advanced wound dressings have been shown to support the needed functions, thereby facilitating UWH. By keeping the wound environment stable and protected, these dressings can reduce the risk of SSIs and promote more efficient healing. Such dressings can stay in place for longer wear as recommended, using gentle adhesives that avoid blistering and peri-wound injuries. They are designed for good exudate management and absorption, and allow patients to shower and have a free range of motion4. Clinical evidence supporting advanced dressing use Clinical studies have demonstrated the benefits of advanced dressings in surgical wound management. For instance, a consensus document by the World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS) highlights that advanced dressings play a vital role in protecting wounds from surgical complications during the healing process. These dressings not only provide a barrier against external contaminants but also create an optimal environment for cellular activities essential for wound repair. Economic considerations and patient outcomes While advanced dressings may incur higher initial costs compared to traditional gauze, the overall economic impact works out to be a lower cost of care when considering the bigger picture. The use of advanced dressings can lead to fewer dressing changes, reduced labour costs for healthcare providers, and a decrease in the incidence of complications that require additional treatments. Moreover, improved patient outcomes, such as faster healing times and reduced discomfort, contribute to enhanced patient satisfaction and quality of life. Implementing best practices in incision care Optimising surgical incision care will require rethinking incision care, dressing protocols and dressing selection. Healthcare providers are on the frontlines and should consider the following best practices: Assessment of wound characteristics: Evaluate the wound's size, location, exudate level, and patient-specific factors to inform dressing selection. Selection of appropriate dressing: Choose dressings that support UWH by maintaining a moist environment, managing exudate, and providing a barrier to contaminants. Minimise dressing changes: Limit dressing changes to when clinically indicated, such as signs of infection or dressing saturation, to reduce disruption of the wound environment. Patient education: Inform patients about the importance of UWH, signs of potential complications, and the need to avoid unnecessary removal and change of the dressing. Monitoring and documentation: Regularly assess the wound and document its progress to ensure timely identification of any issues and to adjust care plans accordingly. Making incision care matter Surgical incision wounds should no longer be the forgotten aspect of wound care. By rethinking incision care and prioritising the selection of advanced dressings that facilitate undisturbed wound healing, healthcare providers can improve patient outcomes, reduce complications, and achieve more efficient use of healthcare resources.

-

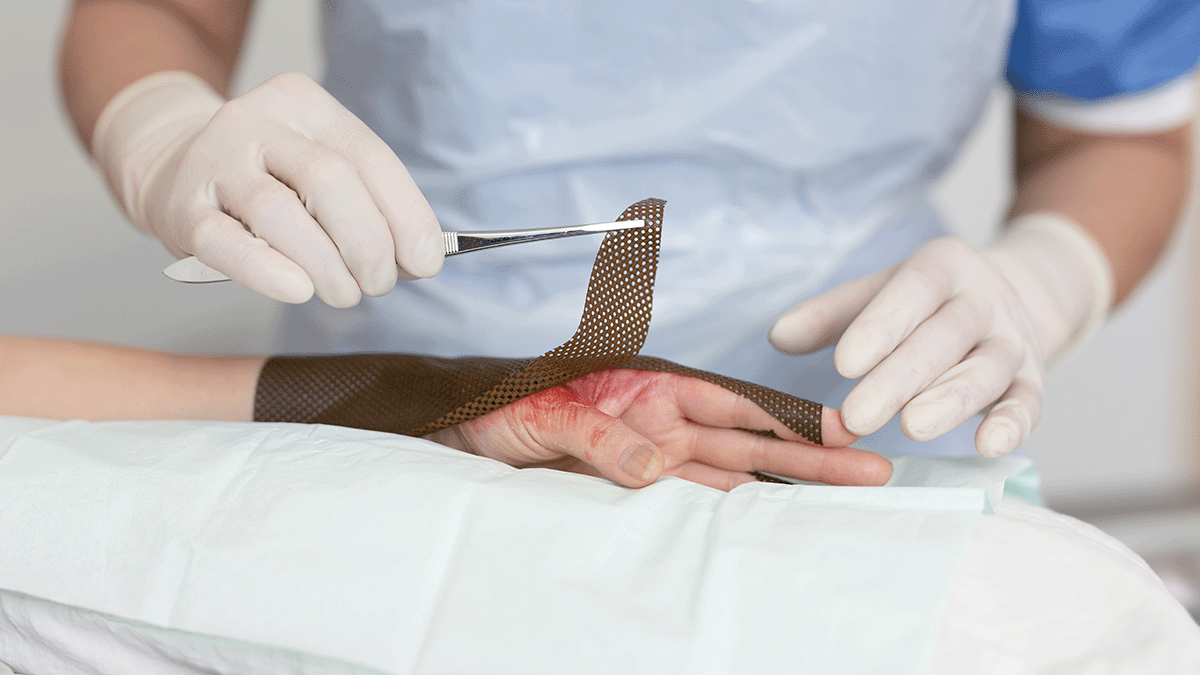

Wound care | 5 min read Cost-effectiveness of burn dressings

Providing cost-effective burn care is a multifaceted challenge that requires a comprehensive evaluation of various treatment modalities, particularly the selection of appropriate dressings. The choice of dressing not only influences the healing trajectory and can influence the overall cost of care. A thorough understanding of the cost-effectiveness of different burn dressings is essential for optimising patient outcomes while sustaining cost-effective care. Understanding burn wound management Serious burn wounds require complex and long-term management, potentially involving long hospital stays, time-intensive surgical and non-surgical treatments, pain management and rehabilitation. All of these have associated costs that result in burn care being expensive1. The mean cost of burn care in a burn centre is more than three times higher than the mean cost of burn care in a general hospital. The complexity and multidisciplinary nature of burn wounds make them particularly challenging, as they require comprehensive management to prevent complications, such as infections, delayed healing, and excessive scarring. Burn dressings are one key element of this management, helping to provide a moist wound environment, protecting the wound from external contaminants, and delivering antimicrobial agents when necessary. But not all burn dressings are created equally. How can the cost-effectiveness of a burn dressing be measured? Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of burn dressings The cost-effectiveness of burn dressings is determined by analysing both direct and indirect costs associated with their use. Direct costs address the price of the consumable products used at each dressing change. Indirect costs include factors, such as associated labour cost, the length of hospital stay, incidence of infection, the need for additional treatments or surgeries, and overall impact on the patient’s quality of life. A study published in the Journal of Burn Care & Research compared the cost-effectiveness of a silver-containing soft silicone foam dressing to silver sulfadiazine cream in patients with partial-thickness burns2. The randomised, multicenter trial found that the silicone foam dressing was more cost-effective, primarily due to reduced frequency of dressing changes and lower associated labour costs. Patients treated with the silicone foam dressing also experienced less pain and greater comfort, contributing to improved patient satisfaction and potentially faster healing times. Another prospective, randomised controlled trial3 evaluated four commonly used burn dressings in an outpatient setting. The study assessed factors, such as healing time, pain during dressing changes, and overall cost of treatment. The findings highlighted significant differences in performance and cost among the dressings, underscoring the importance of selecting dressings based on individual patient needs and specific wound characteristics to optimise both clinical outcomes and cost-efficiency. Total cost of care considerations When determining the most cost-effective dressing, it is important to adopt a holistic perspective that considers the total cost of care. This approach involves evaluating not only the unit cost of the dressing but also the broader economic implications of its use. For instance, a dressing that is more expensive per unit may prove to be more cost-effective in the long run if it leads to faster healing, fewer complications, and reduced need for additional interventions or hospitalisations. That is, some advanced dressings may have higher upfront costs, but their effectiveness in promoting healing and preventing complications can result in overall cost savings. Balancing cost and clinical outcomes Balancing cost considerations with clinical outcomes and efficacy is an increasingly common challenge in healthcare. Rising demand weighed against financial and resource constraints make cost containment a watchword throughout the healthcare sector. While cost is a critical factor, cost containment cannot be the sole consideration if short-term costs remove focus from long-term patient outcomes. From a procurement perspective, less expensive dressings selected solely as a cost-cutting measure can lead to higher costs in the long run, which runs contrary to the principles of value-based healthcare. Value-based healthcare (VBH) aims to achieve the best possible outcomes with existing resources, which requires looking at the big picture. With regard to dressings, a holistic approach to understanding dressing properties demands calculating for factors beyond just price. That is, what is the total cost of healing a wound? Other factors to consider in making such a calculation include characteristics, such as dressing wear time, which affects the frequency of dressing change. Fewer dressing changes reduces the number of dressings required and the time nurses spend changing dressings. Because the least expensive dressing is not necessarily the one that adds the most value, decisions regarding dressing selection should be individualised. In the case of burn dressings, taking into account the specific characteristics of the burn wound, patient preferences, and the clinical setting are important in balancing cost and clinical outcomes. Comprehensive burn care demands total cost of care considerations Providing cost-effective burn care is about more than surface-level, cost-per-unit calculations. Comprehensive burn care demands comprehensive evaluation of the total cost of care associated with different dressing options. By considering both direct and indirect costs, as well as the clinical effectiveness of each dressing, healthcare providers can make informed decisions that optimise patient outcomes while ensuring cost-effective solutions.

-

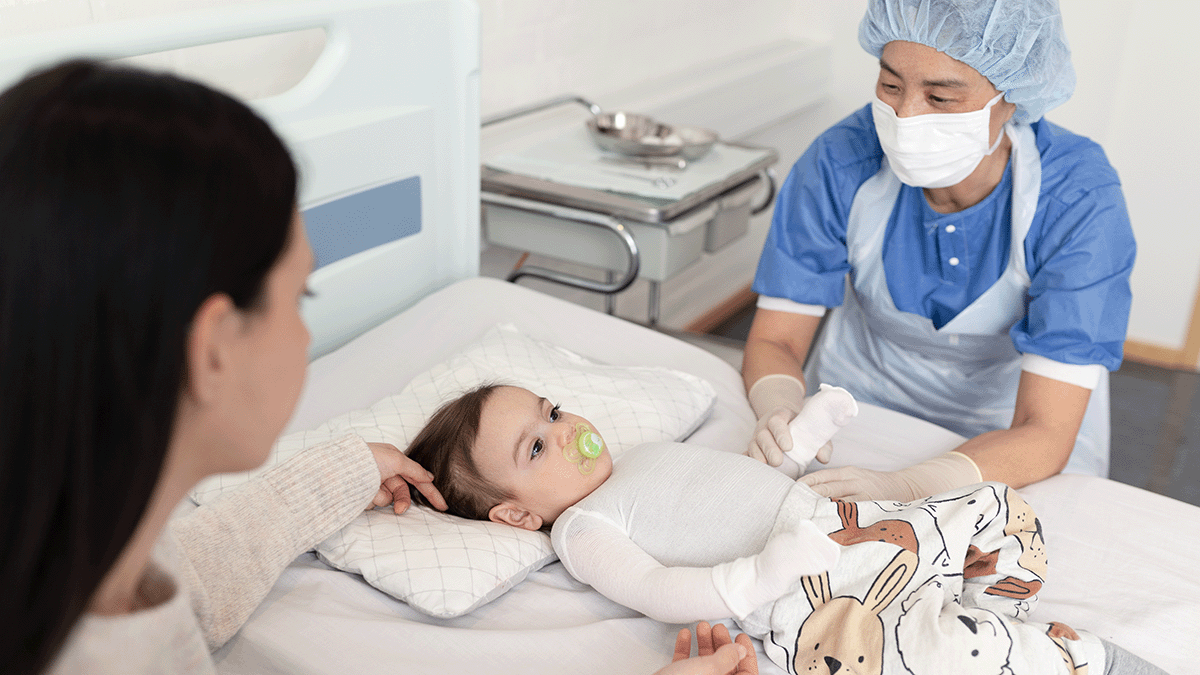

Wound care | 4 min read Burn dressings for children burn patients

Children are especially at risk for burn injuries. According to the European Burns Association (EBA) Guidelines1, scalds account for a substantial proportion of burn injuries in children, underscoring the need for targeted prevention and specialised care strategies. Specialised care in collaboration with carers Caring for paediatric burn patients requires a multidisciplinary approach involving specialised healthcare professionals working in close collaboration with parents and caregivers. The EBA states that such collaborative care is important for addressing the unique physiological and psychological needs of children with burn injuries. Specialised professionals, including paediatricians, burn care nurses, psychologists, and physiotherapists, play integral roles in developing comprehensive treatment plans, ensuring that both medical and emotional aspects of recovery are addressed. Psychological effects of burns on children Burn injuries can be a traumatic experience for children, often leading to anxiety, fear of pain, and feelings of loss of control and impaired autonomy. The EBA Guidelines highlight the profound psychological impact that burn injuries and subsequent treatments can have on young patients. This can be amplified by any need for hospitalisation. Children may experience heightened stress during procedures, dressing changes, and interactions with unfamiliar medical environments. Addressing these psychological challenges is essential for promoting effective healing and long-term well-being. Assessing pain in paediatric patients Accurate pain assessment in children is vital for effective pain management. Several tools have been developed to evaluate pain levels in paediatric patients, with the FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) score being among the most widely used. The FLACC scale assesses five criteria, each scored from 0 to 2, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 10. This tool is particularly useful for young children or those unable to communicate their pain verbally, allowing healthcare providers to tailor pain management strategies appropriately. Appropriate dressing selection to minimise pain and anxiety Choosing the right dressing is another important component of paediatric burn care, as it can significantly influence pain levels, anxiety, and overall patient satisfaction. The EBA Guidelines recommend selecting dressings that are gentle on the wound and surrounding skin and can be left in place for several days. Such dressings minimise the frequency of dressing changes, reducing the associated pain and anxiety for the child. Advanced silicone-based dressings do not adhere to the moist wound bed, adhere gently to dry skin and minimise pain and damage on removal and are thus preferred to support optimal healing and patient comfort, particularly for children. In fact, in a recent consensus of burn surgeons from the Asia-Pacific region2, Mepilex Ag dressings were specifically cited and highly recommended because they adhere gently, absorb exudate and deliver silver to the wound, contributing to infection reduction. It was specifically recommended for paediatric patients due to the reduced pain reported on dressing removal. The importance of parent and caregiver education Educating parents and caregivers is a cornerstone of effective paediatric burn care. The EBA states that informed and involved caregivers can better support the child's recovery process. Education should encompass wound care techniques, signs of infection, pain management strategies, and the importance of follow-up appointments. Empowering caregivers with knowledge gives a sense of control and competence, which can positively influence the child's emotional and physical healing journey. Guidelines and specialised care for best paediatric burn outcomes Paediatric burn injuries present unique challenges that require specialised and comprehensive care approaches. By adhering to established guidelines, such as those provided by the European Burns Association, healthcare professionals can effectively address the complex needs of paediatric burn patients. Through specialised, expert care, appropriate pain assessment tools, careful selection of dressings, and robust caregiver education, the journey toward recovery can be made less daunting for both children and their families.

-

Wound care | 4 min read Making burn treatment less painful

The pain of burn treatment Pain is prevalent among burn survivors, with up to 48% reporting ongoing discomfort from their injuries.1 Dressing changes cause a reported 74% of patients to experience moderate to severe pain.2 This pain is more than simply discomfort; it can actively impede the healing process. Elevated pain levels can lead to increased stress responses, which may slow wound healing, and contribute to the development of chronic pain. With delayed wound healing there is also an increase in the risk of scarring. Therefore, addressing pain management affects patient outcomes burn care and healing. The role of dressing selection in burn care pain management The choice of dressing determines a great deal in terms of whether it contributes to exacerbating or alleviating pain during treatment. Gauze in combination with silver sulfadiazine (SSD) cream or bacitracin often requires frequent changes. These frequent interventions can disrupt the wound environment, potentially leading to increased pain and delayed healing. Moreover, some traditional dressings may adhere to the wound bed, causing significant discomfort upon removal. In contrast, modern silver-containing dressings have been developed to address these issues. These advanced dressings are designed to reduce adherence to the wound bed, minimising pain during dressing changes. Additionally, they often allow for longer intervals between changes, supporting undisturbed healing and reducing the frequency of painful interventions. Benefits of silver-containing dressings over SSD cream Silver sulfadiazine has been a standard topical antimicrobial agent in burn care for decades. However, recent studies have highlighted limitations associated with its use. For instance, SSD cream requires daily application and dressing changes, which can be painful and labour-intensive, particularly when frequent dressing changes disrupt undisturbed wound healing. Furthermore, some research suggests that SSD may delay wound healing and increase the risk of infection compared to modern alternatives. Silver-containing dressings offer several advantages over SSD cream. These dressings provide sustained antimicrobial activity, maintaining a moist wound environment conducive to healing. They also require less frequent changes—often every few days instead of daily—thereby reducing the patient's exposure to contaminants and painful procedures. A comparative study found that silver-containing dressings are superior to SSD cream in managing superficial partial-thickness burns, leading to faster healing times, fewer dressing changes, and reduced pain during changes.3 In addition, advanced dressings, such as Mepilex Ag, which feature a silicone wound contact layer, offer additional pain reduction. A silicone contact layer adheres gently to the skin without sticking to the wound and can be easily removed without damaging the skin. Characteristics of an ideal burn dressing The six key characteristics of an ideal burn dressing, ranked by importance, according to a global survey of burn care experts4 are: Anti-infectiveness Pain-free dressing change Pain reduction Lack of adhesion to wound bed High absorbency Requirement for fewer dressing changes Modern silver-containing dressings with a silicone contact layer align well with these criteria, offering non-adherent surfaces, sustained antimicrobial activity, and the capacity for extended wear. By incorporating these dressings into burn care protocols, healthcare providers can enhance patient comfort, reduce the trauma associated with treatment, and promote more efficient healing. Cost-effectiveness of modern dressings While the initial cost of advanced silver-containing dressings may be higher than traditional options, they can be more cost-effective in the long run. The reduction in dressing change frequency decreases the labour and resources required for wound management. But the cost of the dressing is only one consideration. By minimising pain and trauma, these dressings can reduce the need for pain medication, potentially shorten hospital stays, and increase patient compliance. Atraumatic dressings also lower the risk of complications, which can lead to further cost savings. Taking away the pain and trauma from burn treatment Advancements in burn care have shifted the focus toward treatments that not only promote healing but also minimise pain and trauma for patients. Transitioning from traditional SSD cream to modern silver-containing dressings can also offer additional benefits, including fewer required dressing changes, and improved healing outcomes. By adopting these advanced dressings, healthcare providers can enhance the quality of care for burn survivors, facilitating a less traumatic, less painful journey to healing.

-

Wound care | 5 min read Minimising risk of infection in burn care

Burn injuries and burn care According to the European Burns Association, a burn is a complex trauma that requires multidisciplinary and continuous therapy.1 The complexity of burn care is compounded by the high risk of infection for burns injuries, with burn wound infection and sepsis being among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in burn patients.2 Key burn care and infection prevention strategies Key strategies for burn care and infection prevention from the European Burns Association's "European Practice Guidelines for Burn Care" (Version 4, 2017)1 indicate that there are many effective ways to approach minimising risk of infection in burn care. Some of these strategies include: Rapid initial wound assessment: Prompt and accurate assessment of burn wounds is crucial. Early debridement—the removal of necrotic tissue—reduces the substrate available for bacterial proliferation. The European Practice Guidelines emphasise that "early excision of burn wounds reduces infection rates and improves outcomes." Following debridement, appropriate wound coverage, whether through dressings or skin grafts, is essential to protect the wound bed from microbial invasion. Hand hygiene and aseptic techniques: Strict adherence to hand hygiene protocols is a cornerstone of infection prevention. Healthcare providers should perform hand disinfection before and after any patient contact. Guidelines recommend that "aseptic techniques must be employed during wound care procedures to prevent cross-contamination." This includes the use of sterile gloves, instruments, and dressings during wound management. Environmental controls: Maintaining a clean and controlled environment in burn units is vital. Guidelines highlight the importance of "regular cleaning and disinfection of surfaces and equipment to minimise environmental contamination." Implementing isolation protocols for patients with resistant infections and ensuring proper ventilation systems can further reduce the risk of nosocomial infections. Surveillance and monitoring: Active surveillance of wound cultures and monitoring for signs of infection enable early detection and intervention. Guidelines recommend that "regular microbiological assessments should be conducted to guide targeted antimicrobial therapy." Additionally, monitoring patients' clinical signs, such as fever, increased wound exudate, or unexpected pain, can prompt timely investigations and treatment adjustments. Antibiotic stewardship: Judicious use of systemic antibiotics is essential to prevent the development of resistant organisms. Guidelines advise that "antibiotic therapy should be guided by culture results and limited to confirmed infections." Nutrition: Nutrition supports the immune system and promotes wound healing. Guidelines state that "early nutritional support should be initiated to meet the increased metabolic demands of burn patients." This includes adequate protein intake and supplementation of vitamins and minerals essential for immune function. Patient education: Educating patients and their families about infection prevention measures, such as proper wound care techniques and signs of infection, empowers them to participate actively in their care. Guidelines emphasise that "patient involvement in care can improve compliance with infection control practices." Antimicrobial agents, like silver: Topical antimicrobial agents can play a significant role in preventing wound infections. Silver-based dressings, in particular, have been widely used due to their broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties. The review "Silver in Wound Care—Friend or Foe?"3 discusses the efficacy of silver, noting that "silver-containing dressings can reduce bacterial load in wounds." However, it also cautions about potential cytotoxicity, advising that "the benefits of silver must be weighed against possible adverse effects on wound healing." Therefore, the selection of antimicrobial dressings should be individualised, considering factors such as wound size, depth, and the patient's overall condition. Guidelines recommend antimicrobial dressings for burn wounds at risk of colonisation and infections. Silver sulfadiazine (SSD) cream is a type of antibiotic medication that treats second- and third-degree burns but is associated with the worst outcomes in burn treatment in terms of infection and epithelialisation. Meanwhile dressings containing silver have been found to be superior to SSD and to silver-free dressings for burns in terms of epithelialisation, infection, pain and cost. Proper use of silver-containing dressings is essential for optimal wound healing. Rethinking dressing-change protocols: Because dressing use with SSD requires a higher frequency of dressing changes, there is an increased risk of cross-contamination1. Given the increased awareness around supporting undisturbed wound healing, rethinking the frequency of dressing changes and dressing-change protocols is another key strategy for infection prevention. A multipronged approach to minimising infection risk in burns Minimising the risk of infection in burn care requires a multifaceted approach that encompasses careful wound management, adherence to infection control and hygiene protocols, environmental controls, monitoring, prudent antibiotic use, nutritional support, patient engagement and appropriate use of antimicrobial agents, such as silver-containing dressings when beneficial. By implementing these strategies, healthcare providers can significantly improve outcomes for burn patients, reducing the burden of infections and facilitating optimal healing.

-

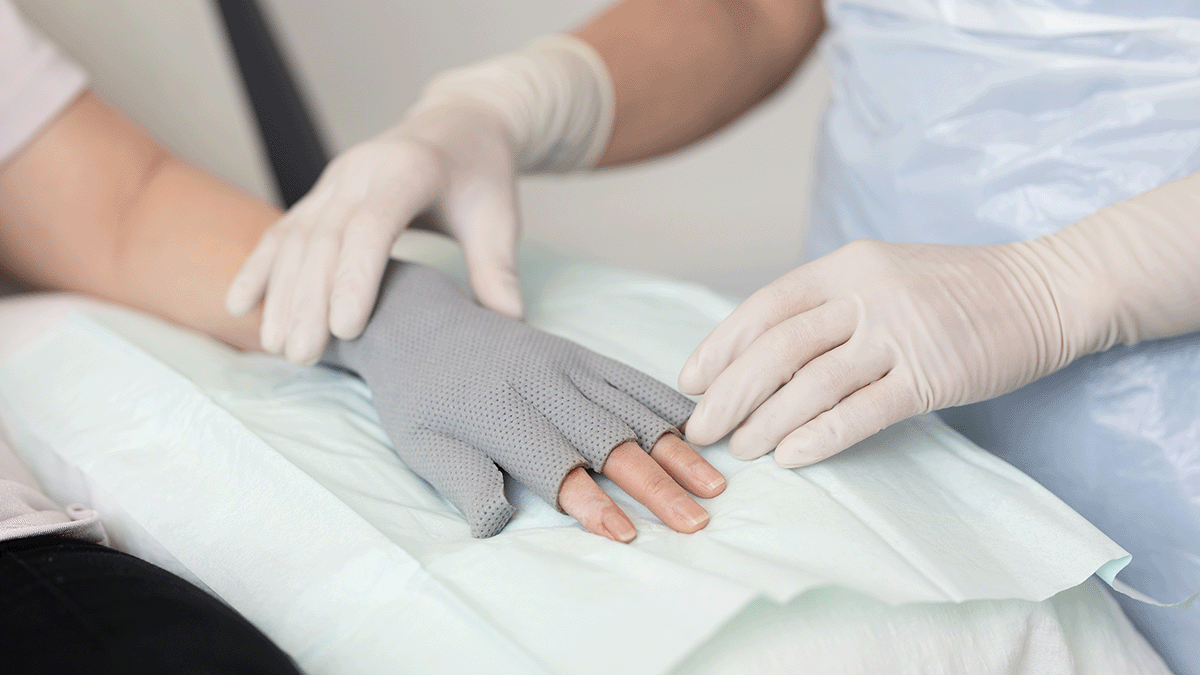

Wound care | 3 min read Characteristics of an ideal burn dressing

Burn injuries represent a significant global health concern, with the World Health Organization estimating approximately 11 million cases annually, leading to around 180,000 deaths. Almost half of these incidents occur in Asia, particularly in countries like China and India1. Effective management of burn wounds is crucial for preventing complications, such as infections, delayed healing, and excessive scarring. A critical component of effective burn management is the selection of an appropriate burn dressing. An ideal burn dressing should possess specific characteristics to optimise the healing process and support positive patient outcomes2. Ideal burn dressing characteristics Through The assessment and treatment of burn wounds in the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region: Consensus meeting report1, Nischwitz et al.’s global burn care and ideal burn dressing survey2, and the International Society for Burns Injuries (ISBI) Practice Guidelines3, a number of key characteristics have been identified that contribute to a shared understanding of what makes up an ideal burn dressing: Lack of adhesion/non-adherence to the wound bed Dressings that adhere to the wound bed can cause trauma upon removal, leading to pain and potential disruption of newly formed tissue. Non-adherent dressings, such as advanced silicone-based dressings, are designed to minimise this, ensuring that the dressing can be changed with less pain and reducing the risk of damaging the healing tissue. Less pain Pain management is a critical aspect of burn care. The dressing should be easy to apply and remove without causing additional discomfort. Additionally, minimising the frequency of dressing changes and using non-adherent materials can further alleviate pain. Fewer dressing changes Not only do patients experience less pain and discomfort from fewer dressing changes, healthcare providers and systems benefit from dressings that can stay in place longer. This likewise allows HCPs to reclaim valuable time. Fewer dressing changes can also contribute to better outcomes by supporting undisturbed wound healing. High absorbency/exudate management Burn wounds produce varying levels of exudate. An ideal dressing should effectively manage exudate by absorbing excess fluid while maintaining a moist wound environment for optimal healing. This balance prevents maceration of surrounding skin and reduces the frequency of dressing changes, minimising disturbance to the wound. Anti-infective/barrier against infection Burn wounds are highly susceptible to infections. An ideal dressing should provide a physical barrier against microbial contamination. Some advanced dressings are impregnated with antimicrobial agents, such as silver, to further reduce the risk of infection. Optimal healing supported by burn dressing choice Selecting the appropriate burn dressing is a key part of effective burn wound management. An ideal dressing should encompass the characteristics outlined above to promote optimal healing, prevent complications, and enhance patient comfort. The choice of dressing may vary based on the specificities of the burn injury, including the depth and extent of the wound, the patient's overall health, and the resources available. Healthcare providers should assess each case individually to determine the most suitable dressing, ensuring that it aligns with the principles of effective burn care and contributes to the best possible outcomes for the patient.

-

Wound care | 2 min read Tips and tricks to prevent pressure injuries in the OR: criteria for assessing patient risk

Watch video -

Wound care | 3 min read Tips and tricks to prevent pressure injuries in the OR: practical steps for nurses and nurse managers

Watch video -

Wound care | 2 min read Venous Leg Ulcers and the never ending problem of leakage

Articles To explore this topic further and freely access thought-provoking articles worth exploring, click the links below. The impact of venous leg ulcers on a patient's quality of life: considerations for dressing selection. VLUs significantly impact patient quality of life due to their chronic nature and associated side effects, including exudate leakage, discomfort and embarrassment. This article from 2023 in Wounds International highlights considerations for VLU management, emphasising the role of dressing selection in improving patient well-being and restoring confidence. [Download] Article - The impact Optimising wound care through patient engagement Enhancing wound care through patient engagement is absolutely crucial for wound healing and, in many cases, alleviating symptoms. This article was collaboratively crafted by healthcare professionals and individuals who use healthcare services, ensuring a patient-centred approach and authentic insights. [Download] Article 2 - Optimising Patient testimonials Exudate leakage can significantly affect a patient’s physical and psychosocial well-being. Hear directly from those living with a venous leg ulcer and this persistent problem. [Video Section] Testimonial video 1 [Video section] Testimonial video 2