The underlying cause of a venous leg ulcer (VLU) is venous disease. Not everyone with vein problems will go on to have a leg ulcer, but everyone with a venous leg ulcer will have signs and symptoms of venous disease that they can trace back over time.2

Epidemiology

Venous leg ulcers are a common, chronic, recurring condition, with an estimated prevalence of between 0.1% and 0.3% in the UK.3 Up to 10% of the population in Europe and North America has venous valvular incompetence, with 0.2% developing venous ulceration.4 In the UK, population prevalence rates for VLUs range from an estimated 1 in every 100 adults, or an approximate annual number of 560,000 individuals with a VLU at any given time.5

As the population ages, all these factors will escalate the cost to the patient and healthcare organisations.

Aetiology

Venous leg ulcers occur due to chronic venous insufficiency (CVI). This happens when the valves of the veins (deep or/and superficial or/and perforator veins) do not function correctly and allow the blood to flow back down (reflux) into the section of vein below.

The pathology can also include venous obstruction (e.g., from blood clotting).6 Venous drainage is impaired, which will lead to venous hypertension.7, 8 Between 40–50% of venous leg ulcers are due to superficial venous insufficiency combined with perforating vein incompetence, but the deep vein system4 is usually normal.

Diagnosis of chronic venous insufficiency is based on clinical characteristics; chronic venous hypertension causes a number of skin changes:

- oedema

- visible capillaries around the ankle

- trophic skin changes such as hyperpigmentation caused by hemosiderin deposit

- atrophie blanche

- induration of the skin and underlying tissue (lipodermatosclerosis) and

- stasis eczema9

In patients with chronic venous insufficiency, the inability of the calf muscles to pump venous blood contributes to the development and delayed healing of venous ulcers. As a result, compression treatment is used to treat lower limb venous insufficiency.5, 10

There are many risk factors for venous ulceration, including heredity, obesity, venous occlusion, and age.4, 10 Importantly, venous leg ulceration reoccurs in up to 70% of people who are at risk.4 More than 95% of venous leg ulceration is in the leg below the knee, usually around the malleoli, and ulceration may be discrete or circumferential.11

Clinical and economic burden

In the UK, as an example, venous leg ulcers have been estimated to cost the National Health Service £941m ($1.2b; €1.1b) per year.12, 13 Most of this healthcare cost is due to community nursing services, as district nurses in the UK spend up to 80% their time caring for patients with leg ulcers.12, 13

Physicians need to be aware that venous leg ulcers have an improved chance of healing if patients can be admitted to hospital for continuous leg elevation.14

Too often, early preventive treatment is not undertaken due to the increasing number of patients with venous leg ulcers and the increasing shortage of hospital beds, the high cost of in-patient hospital care, and the need to maintain independence in the mainly elderly population who suffer from venous leg ulcers.14

Effects on patient quality of life

Venous leg ulceration is often a chronic condition, and patients experience a prolonged cycle of skin healing and then breakdown (read more about the challenges of this cycle). This cycle of wound healing and reversal sometimes repeats over decades, with episodes of infection, all of which can impair quality of life.15

Optimal management and care of venous leg ulcers: Psychosocial and pain responses

Management of leg ulcers occurs mainly in the community, but community nurses and general practitioners have limited time to spend with patients, and this time is usually directed to clinical management15. Psychological and social effects of venous leg ulceration have received little attention in clinical management guidelines but include social isolation, anxiety, and depression, particularly when ulcers are highly exudative and painful.15

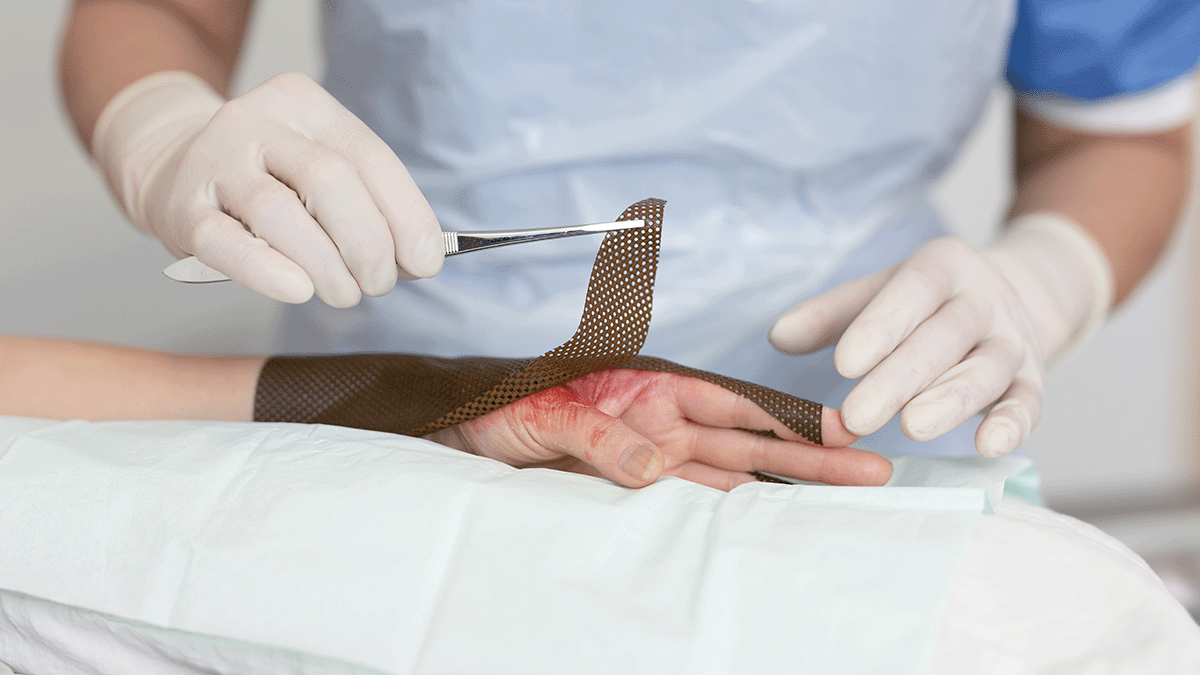

In a recent exploratory study undertaken to compare the pain and stress experiences of 49 patients with chronic wounds being treated with atraumatic vs, conventional dressings during dressing change, acute episodes of pain and stress were much lower in patients receiving atraumatic dressings.

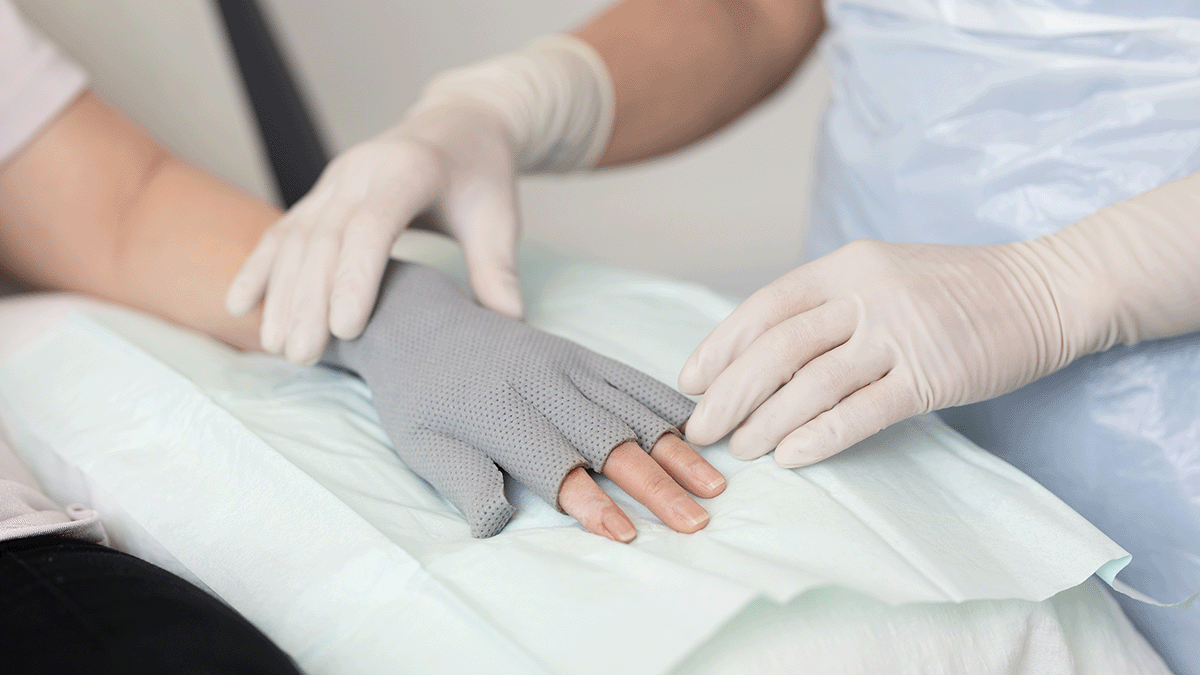

Optimal management and care of venous leg ulcers: Dressing selection and M.O.I.S.T. model

As with most wound types, venous leg ulcers benefit from appropriate dressing selection and implementing a M.O.I.S.T. healing model.

Selecting dressings and M.O.I.S.T. management complement each other. Topical wound therapy options, such as dressings, are selected based on the goals and actions for healing, such as creating a balanced moist healing environment or improving tissue oxygenation, which are two of the key properties of the M.O.I.S.T. model.

The M.O.I.S.T. model is an acronym that stands for:

- Moisture balance: Creating a balanced moist healing environment

- Oxygen balance: Improving tissue perfusion and local oxygenation at the wound bed

- Infection control: Avoiding wound infection or treating an existing infection

- Supporting strategies: Creating a supportive wound environment to stimulate healing

- Tissue management: Removing devitalised tissue and debris, to form healthy granulation and epithelial tissue

M.O.I.S.T. principles can be applied across a range of chronic wounds, including VLUs, and the application of M.O.I.S.T. has been shown to help such wounds “progress toward healing or achieved complete healing”.16